The Photosynthesis Twist That Shaped Human History

What Can Plants Tell Us About Our Diet and the World?

Imagine if plants could tell stories, not just about themselves but about us, our ancestors, and even the climate of the Earth thousands of years ago. Sounds impossible, right? But scientists have discovered that plants leave behind subtle clues through the way they capture sunlight and carbon dioxide. These clues, hidden in the C3 and C4 photosynthetic pathways, help us uncover what people ate centuries ago, how ancient civilizations farmed, and even how climate change might affect our future.

So, what are these mysterious pathways? And why are they important enough to be taught in schools? Let’s explore the fascinating world of plant science, food tracking, and ecological detective work.

C3 and C4 Plants Explained: How Photosynthesis Adapts to the World Around Us

Before we can understand how plants reveal our secrets, we need to understand how they eat! yes, plants eat too! But instead of munching on food like we do, plants use photosynthesis to turn sunlight, carbon dioxide (CO₂), and water into glucose (a type of sugar) that fuels their growth.

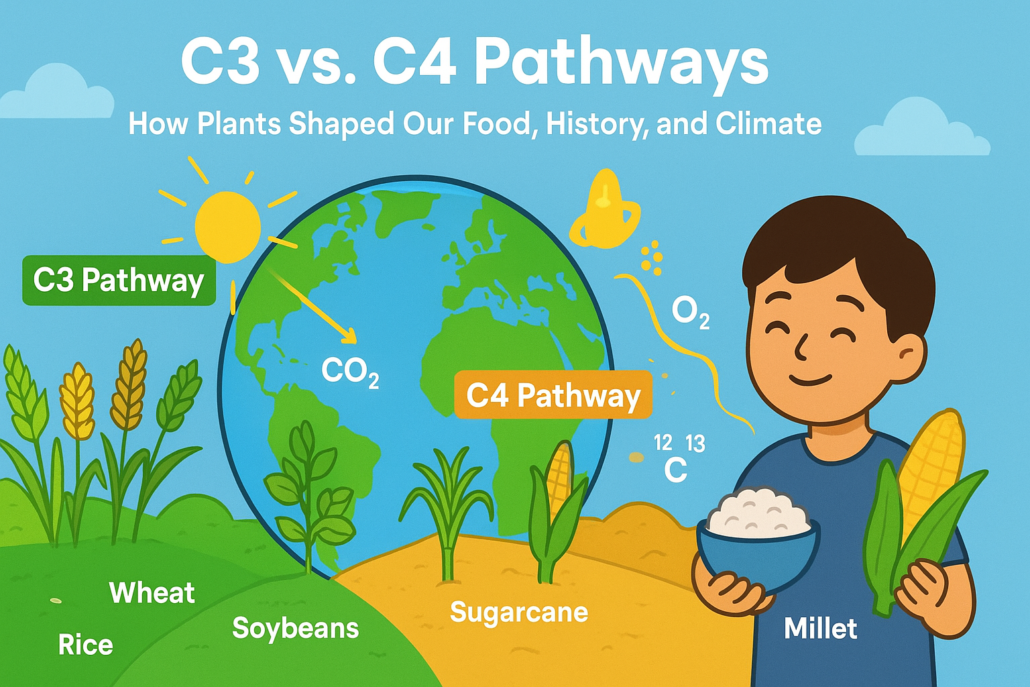

But here’s the twist: not all plants photosynthesize the same way. Over millions of years, plants developed two major strategies to fix carbon from the air:

- C3 Pathway

- C4 Pathway

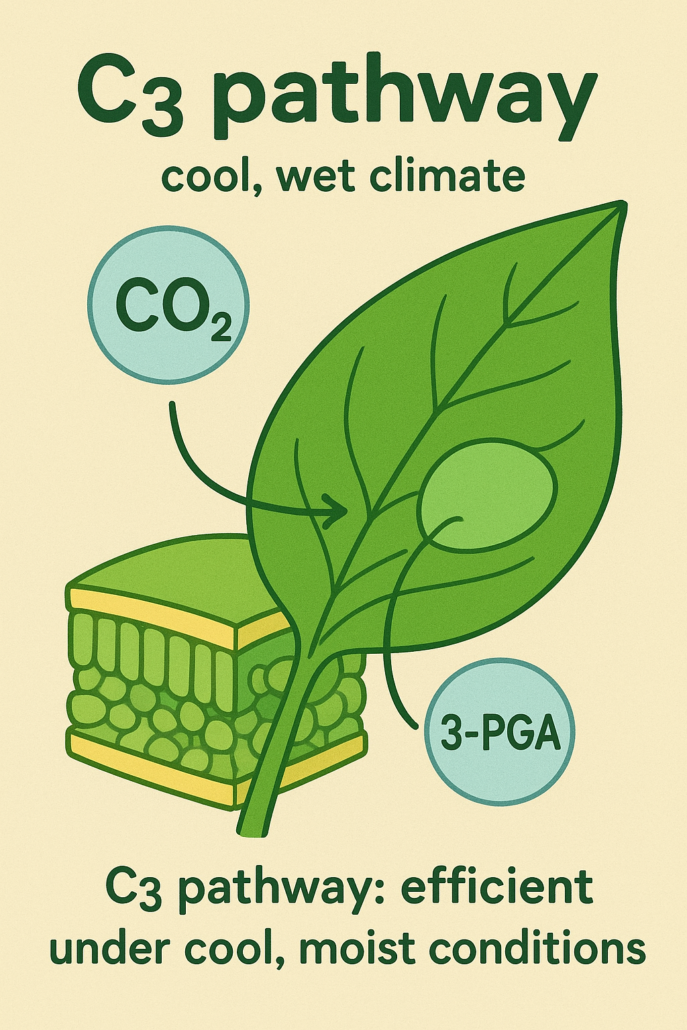

Meet the C3 Plants: The Everyday Performers

The C3 pathway is the most common type of photosynthesis. It is used by about 85% of all plant species on Earth.

In C3 photosynthesis, plants capture CO₂ and convert it into a 3-carbon molecule called 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA).

C3 plants thrive in cool, moist environments where sunlight is not too intense.

Examples of C3 plants:

Wheat, rice, oats, soybeans, potatoes, and most fruits and vegetables.

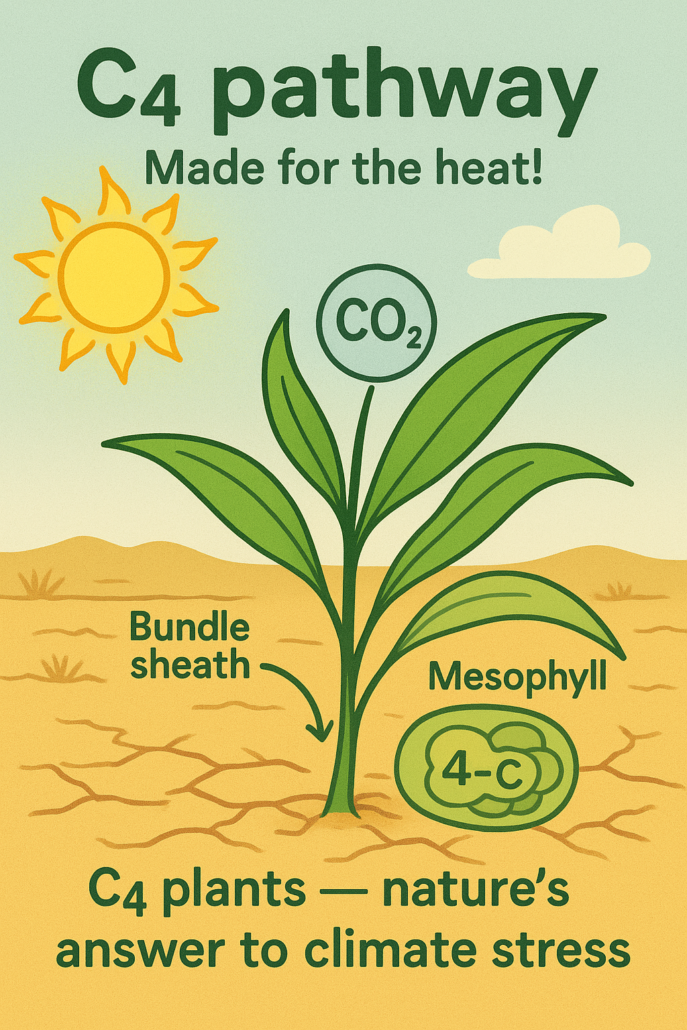

Meet the C4 Plants: The Desert Survivors

The C4 pathway is an adaptation that helps plants survive in hot, dry environments.

These plants convert CO₂ into a 4-carbon compound called oxaloacetate before entering the regular photosynthesis cycle. This extra step makes them more efficient in capturing CO₂, especially under harsh conditions.

C4 plants are more water-efficient and can photosynthesize even when the air is dry.

Examples of C4 plants:

Maize (corn), sugarcane, sorghum, and millet.

From Leaves to Life: Carbon’s Journey Through Us

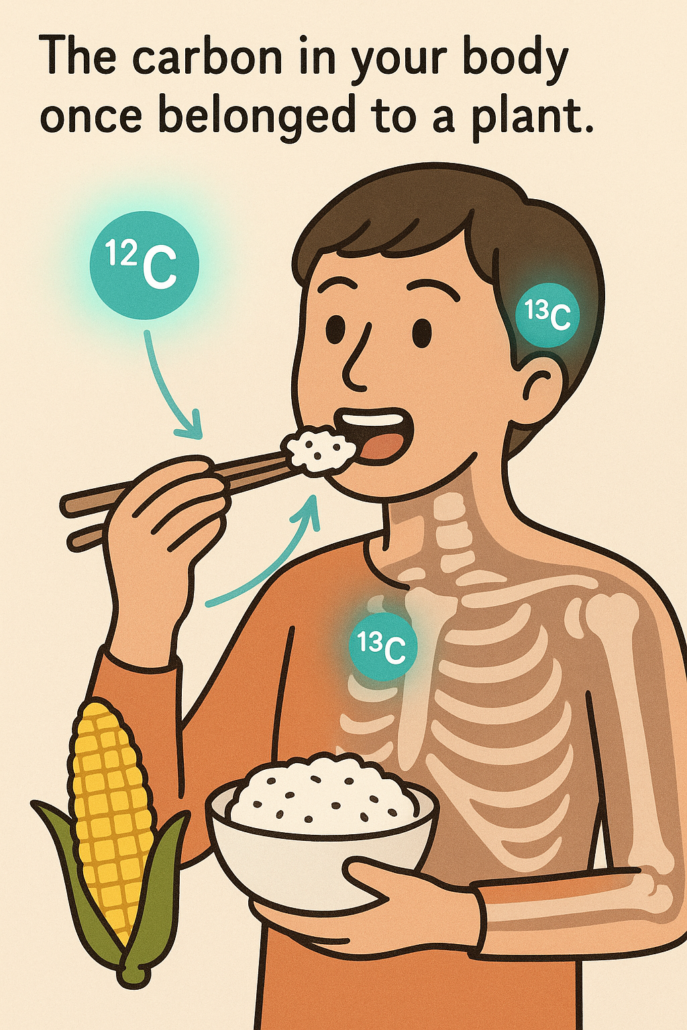

Now that we know how plants make food through photosynthesis, here is something amazing, C3 and C4 plants have different carbon “fingerprints.” When we eat these plants, or animals that ate them, their carbon becomes part of our body. These tiny carbon marks stay in our bones, teeth, and even hair, telling the story of what we eat.

Carbon Isotopes: Nature’s Invisible Markers

When plants absorb CO₂ during photosynthesis, they take in both carbon-12 (¹²C) and carbon-13 (¹³C) which are two stable forms of carbon called isotopes. However, C3 and C4 plants absorb these isotopes differently:

C3 plants prefer ¹²C and have lower levels of ¹³C.

C4 plants absorb more ¹³C and have higher levels of this heavier isotope.

When we eat these plants (or animals that ate these plants), the isotope ratios get stored in our bones, teeth, hair, and even fingernails. By measuring the ratio of ¹³C to ¹²C in biological samples, scientists can track diets and study past civilizations.

This measurement is expressed as δ13C (delta carbon-13) values, which show the relative amount of ¹³C in a sample.

How Does This Help in Tracking Food Habits?

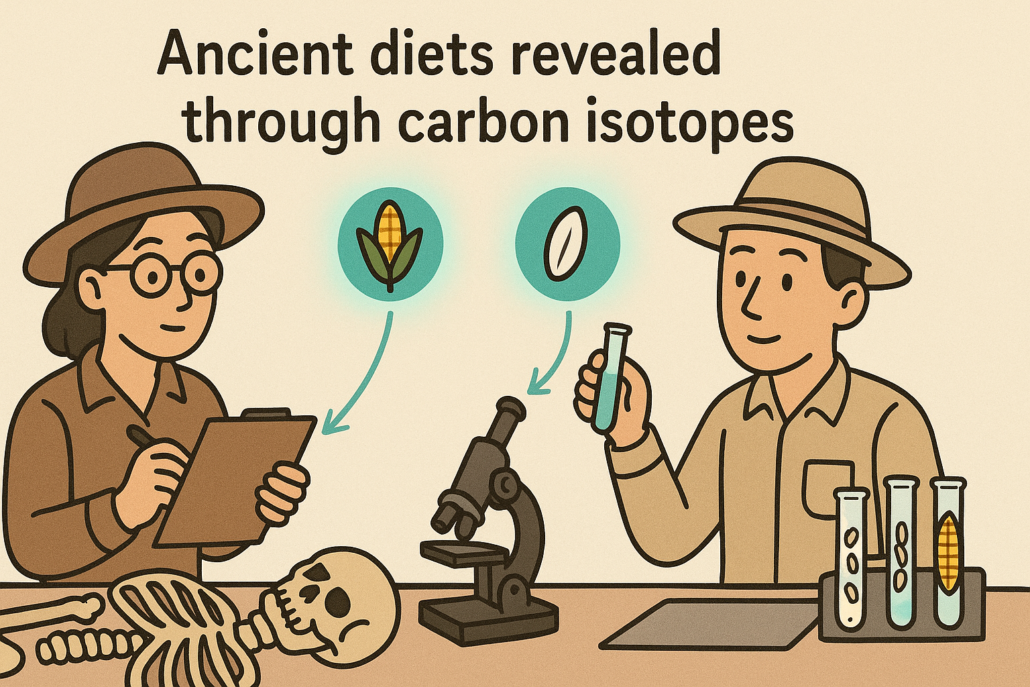

1. Reconstructing Ancient Diets

Archaeologists and anthropologists use carbon isotopes to uncover what people ate thousands of years ago.

- For example, in ancient Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztecs, maize (a C4 plant) was a staple food. By analysing δ13C values in ancient human remains, scientists found higher levels of ¹³C, confirming that corn made up a large part of their diet.

- In contrast, people in Europe and Asia primarily consumed C3 plants like wheat and rice. Their remains show lower δ13C values, indicating a different dietary pattern.

2. Tracking Modern Food Habits

Carbon isotope analysis is not just for ancient history but it can also track modern diets.

- If someone has higher δ13C values, it suggests they eat a lot of corn-based products (like corn syrup, commonly found in processed foods) or sugarcane.

- This technique helps nutritionists and health researchers study the effects of processed foods on health.

3. Forensic Science: Solving Mysteries

Forensic scientists use isotope analysis to identify unknown individuals or track their movements.

- Example: If a missing person had high δ13C values in their hair, it might indicate they lived in an area where C4 crops like maize or sugarcane were common.

This technique has been used in criminal investigations and even to identify unmarked graves from historical events

Connecting the Dots: What C3 and C4 Plants Teach Us About Life on Earth

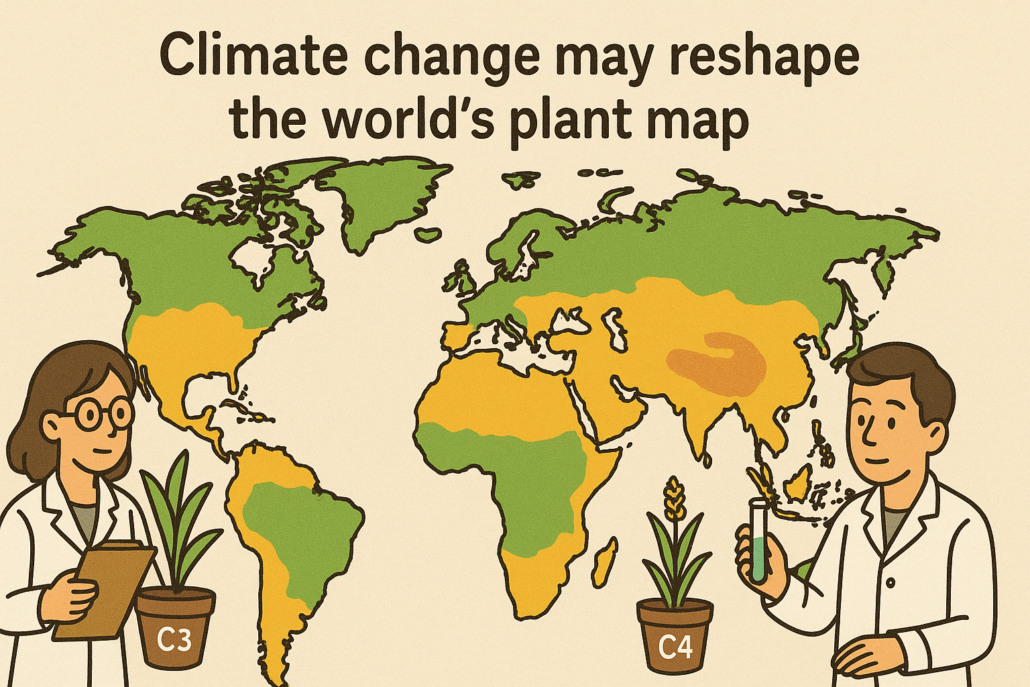

1. Understanding Climate Change

C4 plants are better suited to hot, dry climates because they are more water-efficient. As the Earth’s climate changes, the distribution of C3 and C4 plants is shifting. By studying these shifts, scientists can predict how ecosystems and agriculture will respond to global warming.

- Example: If certain regions become hotter and drier, we might see more C4 plants like maize and sugarcane replacing traditional C3 crops like wheat or rice.

2. Improving Agriculture

Scientists are exploring ways to engineer C3 crops to behave more like C4 plants, making them more efficient and climate-resilient.

- Example: Researchers are trying to develop C4 rice to improve crop yields in warmer climates. This could help address food security in countries that rely heavily on rice.

3. Protecting Ecosystems

By tracking carbon isotopes in plants and animals, ecologists can monitor food chains and track animal migrations. This helps in conservation efforts and understanding how human activities are impacting wildlife.

The Silent Storytellers: How Carbon Remembers Our Past

C3 and C4 plants are more than just green things growing in the ground. They are silent storytellers, holding secrets about our diet, history, and planet. By understanding these pathways, we can resolve mysteries about ancient civilizations, improve modern agriculture, and prepare for the future of our changing world.

So, the next time you bite into a bowl of rice (a C3 plant) or munch on popcorn (a C4 plant), remember you are tasting millions of years of evolution and tapping into a global scientific story!

Why Learn About This in School?

You might be wondering, “Why should I care about C3 and C4 pathways in school?” Here is why:

Connecting Science to Real Life:

Understanding these pathways shows how biology connects with history, climate science, nutrition, and even forensics. It is a perfect example of how interdisciplinary science works in the real world.

Developing Critical Thinking:

Learning about isotopes and photosynthesis is not just about memorizing facts. It teaches us to think critically, analyse data, and solve complex problems skills that are valuable in any career.

Preparing for the Future:

As climate change, food security, and health become global challenges, knowledge about plant biology and carbon cycles will be crucial in finding solutions.

Glossary of Scientific Terms (C3 vs. C4 Pathways)

1. Photosynthesis

The process by which green plants use sunlight, carbon dioxide (CO₂), and water to make food (glucose) and release oxygen.

2. C3 Pathway

The most common form of photosynthesis where plants produce a 3-carbon compound (3-PGA). Best suited for cool, wet conditions.

3. C4 Pathway

An advanced form of photosynthesis where plants produce a 4-carbon compound (oxaloacetate) to capture CO₂ more efficiently. It helps plants survive in hot, dry environments.

4. Glucose

A simple sugar that plants produce during photosynthesis and use for energy.

5. Carbon Dioxide (CO₂)

A colourless gas that plants take in from the air to perform photosynthesis. Humans and animals exhale it.

6. 3-Phosphoglycerate (3-PGA)

The first stable product formed in C3 photosynthesis; it contains three carbon atoms.

7. Oxaloacetate

A four-carbon molecule formed in C4 plants during the first step of photosynthesis, helping the plant trap carbon more efficiently.

8. Isotopes

Atoms of the same element that have different numbers of neutrons. For example, carbon-12 (¹²C) and carbon-13 (¹³C) are two isotopes of carbon.

9. Carbon-12 (¹²C)

A lighter and more common form of carbon used more by C3 plants.

10. Carbon-13 (¹³C)

A heavier and less common form of carbon that C4 plants absorb more than C3 plants.

11. δ13C (Delta Carbon-13)

A way of measuring the amount of carbon-13 in a sample to learn about what types of plants were eaten or present in the environment.

12. Stable Isotopes

Isotopes that do not change or decay over time, making them useful for tracking biological and environmental changes.

13. Archaeology

The study of human history through artifacts and remains, including analysis of bones and teeth to study ancient diets.

14. Forensic Science

The use of scientific methods to solve crimes or identify people, often through analysis of hair, bones, or tissues.

15. Bioapatite

A mineral in bones and teeth that stores chemical information, including carbon isotope ratios, useful for diet and migration studies.

16. Climate Resilience

The ability of plants, animals, or ecosystems to withstand or adapt to changes in climate conditions like drought or heat.

17. Food Security

The availability of food and people’s access to it; having reliable access to enough nutritious food.

18. Evolution

The process by which organisms change over generations due to natural selection and adaptation.

19. Ecosystem

A community of living organisms interacting with each other and their environment (air, water, soil).

20. Interdisciplinary Science

A scientific approach that connects different fields (like biology, chemistry, and history) to solve complex real-world problems.